Phone addiction

Somewhere in the early 2010s, I met Melanie in Barcelona. I was a broke freelance journalist traveling for a workshop and needed a place to stay. I found Melanie on CouchSurfing, and she kindly agreed to host me. Back then, mobile data wasn’t really a thing yet, but Wi-Fi was everywhere: open city networks, cafés. Just not in her apartment.

Melanie was a young American who had moved to Spain a year earlier. She used to work at Apple, which made her one of the early adopters of the iPhone. She told me how she’d hang out with friends at bars or restaurants, but everyone would just be on their phones. They’d even chat privately about people at the table—as if talking behind their backs, while sitting right next to them. She came to hate that, and eventually banned the internet from her home. The evening I spent with her, she knitted and drew,

In the study, the Chinese users ranked among the most addicted. Another small study among 180 Chinese university students found they spent on average 5.5 hours a day on their phones. That is more than one third of their waking hours. To put that into perspective: in 2023, the Chinese government proposed to limit children younger than 8 to 40 minutes of smartphone time a day, increasing the time limit to two hours daily when adult. That is also roughly how much time I spend on my smartphone.

You know what? Let’s get intimate. Here is my data 🤳

Back to the Chinese students: as a result of their smartphone use, some reported mild depression, blurring eyesight, sore fingers, distorted sense of time, poor sleep or feelings of anxiety when scrolling. But not everone is bothered by it. One student put it this way: “I know that using a smartphone for 6 hours daily is a bit too much [but] since I am so happy when playing on the device, and making changes will be painful, why do I need to control my usage? If the purpose of life is to pursue happiness, smartphones can indeed fulfill my needs.” And honestly, who’s to say they are wrong?

A very persuasive design

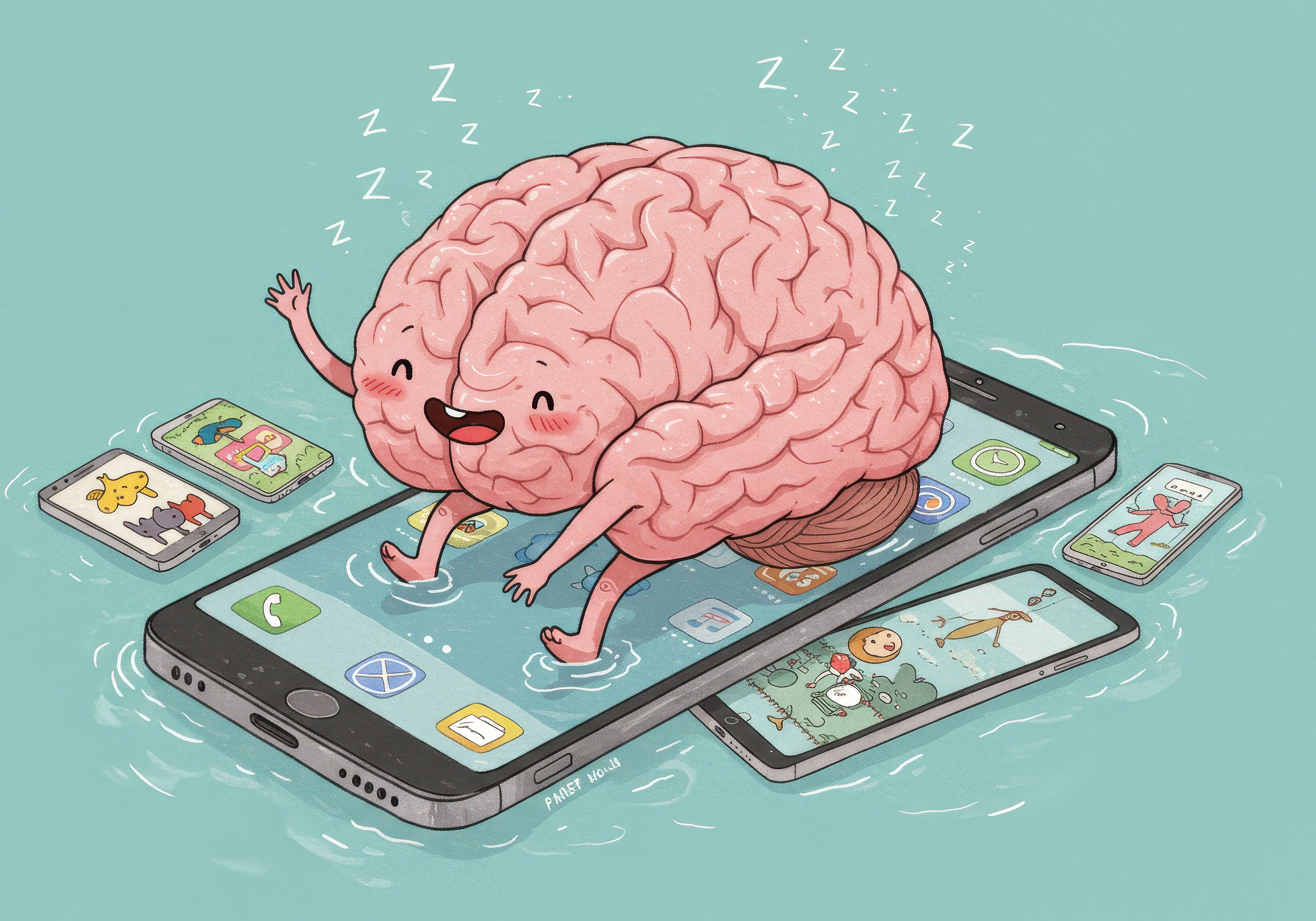

The main reason your phone brings you that hit of joy in the moment is because it’s intentionally designed to trigger your dopamine reward centers. It’s not that the phone is incredibly useful. It’s just incredibly good at creating compulsive behavior.

This is called persuasive design, and it’s what Duolingo uses to keep you coming back to your language lessons. But even well-intentioned features, like Facebook’s "like" button, originally meant to spread positivity, ended up fueling also feelings of comparison or envy. In the battle for our attention, platforms deploy all kinds of design tricks to keep us hooked: endless scrolling, endless recommendations, and so on.

This is actually also a field of study, called captology. It explores how interactive technologies are built to shape what we believe and how we behave. It observes that we humans respond to computers as though they were well ... humans.

Take a simple slot machine with two animated characters cheering you on every time you win. It is their job to persuade you to keep pulling that lever over and over again. Or when a chatbot that says “I’m sorry.”, making it seem like it understands how you feel. Spoiler alert: it doesn’t.

Other ‘captologically enjoyable’ experiences include infinite scroll, or the bright attention-grabbing colors used in the apps. Or just fact that you carry the device on your person everywhere you go.

“When you pack a mobile persuasive technology with you, you pack a source of influence. At any time the device can suggest, encourage, and reward.”

~ B. J. Fogg, Persuasive Technologies

As an investigative journalist I often ask myself the question who is benefiting (and despite of that yes my life is still fun.) According to several — let’s say “less than perfect” — data sources, rocking the charts of most downloaded apps are Instagram, TikTok, WhatsApp, Facebook, and ChatGPT. In other words, a large chunk of our phone time is spent inside the carefully crafted gardens of Meta and a few others. These apps are packed with persuasive design, and none of them let you opt out of it. I can’t tweak or change how they work. There is no choice. Which makes me believe, that my smartphone isn’t really mine at all.

But it could be! We could design apps that put users in control. For example by giving us the option to:

build in stopping points—so scrolling actually ends

hide like, view, or comment counts when you choose to

set time limits for how long you use certain apps

customize how an app looks and behaves

fine-tune how content is personalized

or even just get a gentle reminder to take a break

These are not radical ideas. But sadly, I don’t see them being adopted anytime soon. As long as our attention keeps making these companies richer, they’ll keep mining it—relentlessly.

Leave my attention alone

Right now, the only real weapon I feel I have is boycott. That’s why I’ve chosen to completely disconnect from my smartphone between 8PM and 10AM. I put it in the designated wooden box, close the lid shut and just like that ✨ it stops existing.

Then I sit on the sofa with a cup of tea and feel a small wave of panic. What now?

So I sit a little longer. And slowly, ideas start to arrive. I get up and browse the bookcase. I sit at the piano. I take out my watercolors and play kindergarten for a bit. I practice handstands. And by the time I go to sleep, I feel so much better knowing I didn’t spend my last hours of the day numbing my brain with dopamine triggers.

Later this year, I plan to take things even further—go for a long hike in the mountains, pack a tent and some food, and spend at least a week off the grid, surrounded by nothing but nature.

I can’t wait.